Interview with Barry Joseph, author of Matching Minds with Sondheim: The Puzzles and Games of the Broadway Legend

Welcome, CFIA readers! The Center for Immersive Arts is a project to preserve and explore the history of immersive arts. You can learn more about the CFIA by subscribing to the newsletter, and get behind-the-scenes updates and info by supporting my work on Patreon.

I chatted with Barry Joseph about his upcoming book, “Matching Minds with Sondheim: The Puzzles and Games of the Broadway Legend”, releasing in May of 2025 with Applause Books. The book explores Sondheim’s legendary, never-before-shared puzzle scavenger hunts, based on an exploration of Sondheim’s personal collection of materials, interviews with friends and family, and a bit of contemporary “experimental archaeology.”

From the publisher’s site:

“By near-universal consensus, Stephen Sondheim was the greatest musical theater composer of his generation—celebrated, among other things, for the wit, sophistication, and intricacy of shows from West Side Story to Sunday in the Park with George. A less well-known but nonetheless key facet of his legacy was his lifelong obsession with games, puzzles, and all other manner of brain-twisting diversion—from crosswords and jigsaws to murder mysteries and party games—which he avidly pursued not only as a participant but as a deviser-creator. Following Sondheim’s death in 2021, countless friends and collaborators shared fond remembrances of the scavenger hunts he would plan and the hand-crafted games he gifted to those he was closest to.

“Matching Minds with Sondheim is a journey into this rich but largely unmapped aspect of the composer’s creative life, from his teenage years sending puzzles to the New York Times and board games to Milton Bradley until his final years designing treasure hunts and visiting escape rooms. For the first time, it offers an enthralling tour of what Sondheim described as his “puzzler’s mind,” helping readers to better understand the man, his work, and—if they accept the challenge—themselves. Gaming expert and theatre fan Barry Joseph draws from over eighty years of Sondheim’s activities, collecting his extremely rare and never-publicly-seen puzzles and game designs, scores of original interviews with the celebrity friends who played them, deep dives into Sondheim-related archives from around the country (such as over 100 hours of interviews at Yale University that only became available last year), and analysis from both puzzle designers and theater professionals from around the world. Matching Minds will do more than describe Sondheim’s work: It will allow readers to match minds with the master by attempting to solve some of Sondheim’s best puzzles and provide the materials and instructions for bringing his games into their own homes.“

Though legendary for his work in musical theater, Stephen Sondheim was also a lifelong puzzle-lover. He crafted scavenger hunts for friends and colleagues that became legendary in the New York theater scene — yet for a man so famous for his creative work on stage, there is little publicly known about his private puzzle design work. This was a source of frustration for Joseph.

“[In interviews,] everyone said, ‘Sondheim, you love puzzles, you love games.’ And he would say, ‘Yes.’ And they would say, ‘Okay—let’s talk about your musicals,’” Joseph said.

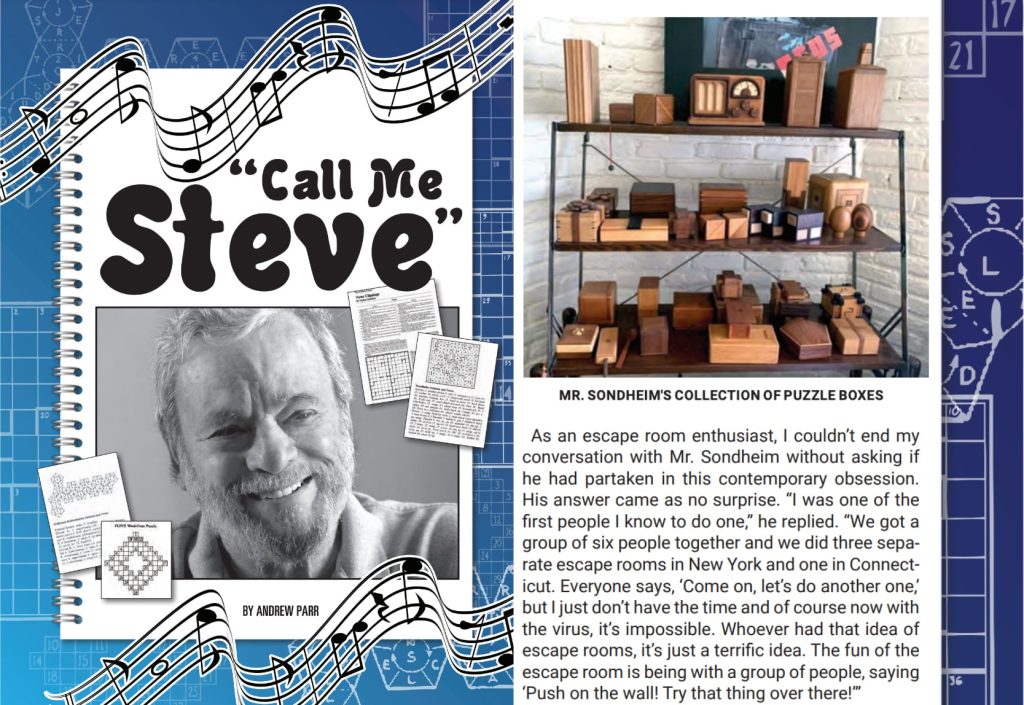

It’s surprising, given Sondheim’s deep knowledge of puzzles and games, and his professional expertise in the field. In addition to his legendary puzzle hunt work, Sondheim was the founding puzzle editor at New York Magazine in the late 1960s, where he introduced the British cryptic crossword to America. In 1973, he and Anthony Perkins wrote the movie The Last of Sheila, a whodunnit murder mystery set amidst a puzzle-heavy scavenger hunt. (The film was an influence on the Knives Out movies, and Sondheim has a cameo in Glass Onion.) He enjoyed video games, and in the years leading up to his death, he was a fan of escape rooms.

What is a “Puzzle Hunt”?

A puzzle hunt is a scavenger or treasure hunt with multiple sequential puzzle clues. Sometimes, a puzzle hunt contains a “meta puzzle”, which uses elements from each of the solved clues to form one final puzzle, leading to the final treasure. Puzzle hunts can take place in a single space like a museum, or may be spread out across a whole city. In Sondheim’s movie The Last of Sheila, the players dock at various cities on the French Riviera, roaming the streets in search of answers to the puzzles, all while hoping their secrets remain hidden.

This unexplored aspect of Sondheim’s career intrigued Joseph, who is also a game, puzzle, and experience designer.

“I’ve always been a Sondheim fan,” Joseph said. “And have also been a game designer and a promoter of games-based learning and social impact games for decades. I never saw an opportunity to combine those two, and I never thought I would.”

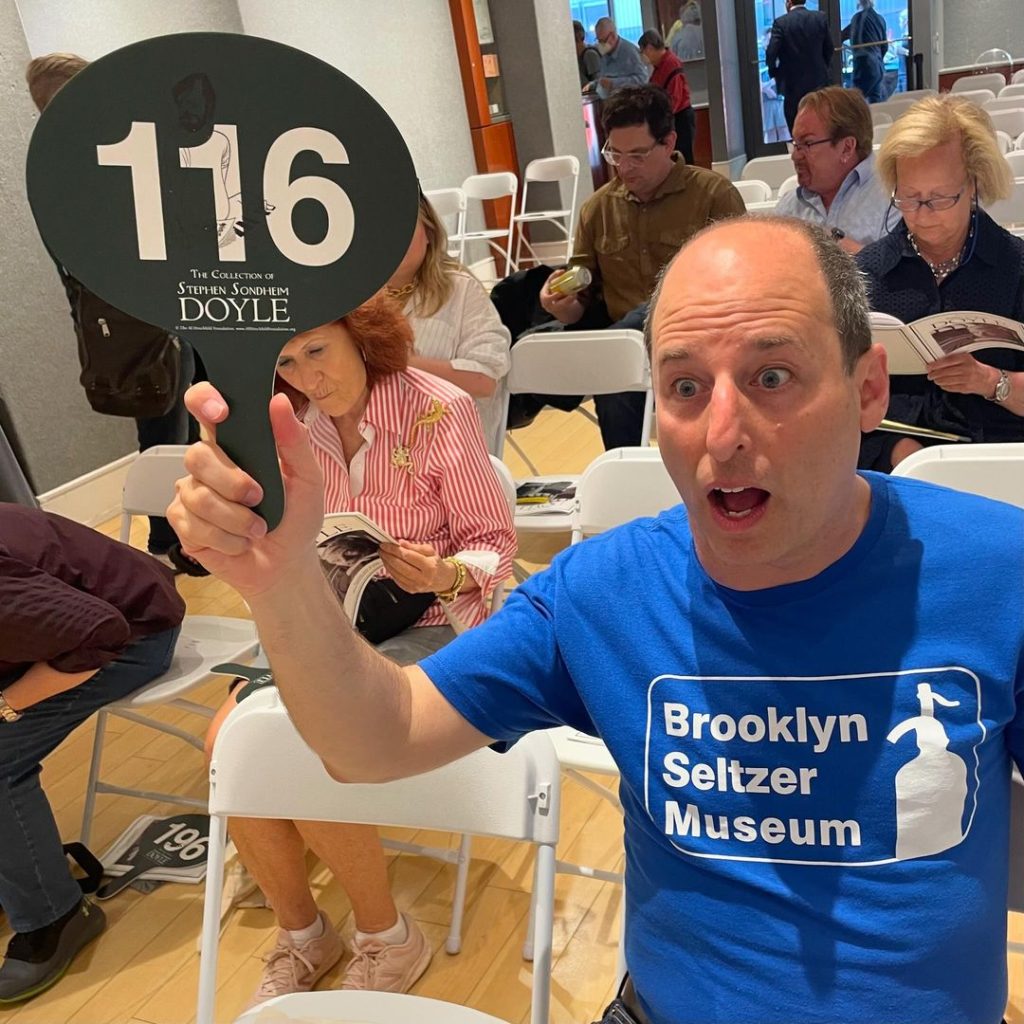

The first inkling that there might be more to discover about Sondheim’s puzzle design work came from reading an interview in which Sondheim mentioned considering working leaving Broadway to work in video games. Joseph wanted to dig deeper. He was able to acquire puzzle-related magazines and other materials from Sondheim’s estate when his collections went up for auction at Doyle Auction on June 18, 2024.

According to Joseph in an interview with The Sondheim Hub, “I counted roughly 3500 individual items that were up for auction from the two homes. 1800 of them were puzzles and games. More than 50%. … And they trace his life from when he was a teenager until he passed away. And because his stuff was private mostly — playing games with friends, making a parlor game with friends, being invited to make a treasure hunt for friends — most of the stuff wasn’t available in a public way, and most of it hasn’t been stored anywhere.”

Through hours of original interviews with Sondheim’s friends and collaborators, Joseph uncovered vital details about the various puzzle hunts Sondheim designed, including information about the clues, the games’ structure, and the distribution of the games throughout the buildings they were set in. However, this was only a view into Sondheim’s design work from the perspective of a player — Joseph wanted to understand Sondheim’s point of view as a designer.

![Ronan Farrow on Twitter writes, "This was real. Steve loved video games and took them seriously as an art form. Especially adventure games—an extension of his love of math and puzzles and, later on, escape rooms, which he and his partner Jeff really crushed. We talked about his love of Myst a lot over the years." He is quoting Sarah Elmaleh, who writes, "I'm sorry WHAT. WAT.

Babe I love Sunday as much as the next person, like LOTS, but a world in which Sondheim made games instead is a bit goddamn dazzling to consider." She is responding to a quoted text that reads, "June 12, 1982. With Sondheim, 52, in "a pretty dark place" after the failure of "Merrily We Roll Along" in 1981 — he's considering giving up theater to make video games — Lapine, 33, a downtown up-and-comer, anxiously heads to their first meeting "through a huge [Text is cut off]"](https://cfia.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/farrowsondheim.jpg)

“The party planners who were hired to work with him to support these events allowed me to understand the process that went into it,” Joseph said. “I know how he developed them. I know that he went around the space and he looked for opportunities. He iterated, live with people in a playtest — I call it a playtest, he called it a dress rehearsal. He did all the graphic design, the visual design. But what went on in his mind? No one could tell me this.”

Joseph realized that to truly understand these games, they needed to be not only pieced together on paper — but replayed.

On paper, it’s possible to understand the structure of a puzzle game, tease apart its components, and see how different puzzles flow into each other and reference one another. But it’s only in the act of playing a game that it comes alive. Sondheim’s games were designed to be interactive, allowing players to experience realizations as they solved puzzles in a physical space. Replicating some of these conditions and observing people at play — the puzzle hunts were replayed on Zoom calls rather than in their original, in-person locations, and players received paper packets in the mail beforehand — allowed Joseph to gain a deeper understanding of the games’ designs.

“I had to watch people do it, and I wanted people who did puzzles,” Joseph said. “I invited Andrew Parr, who did the last major Games interview with Sondheim. His fiancee, Jess Butler, joined. Mark Halpin, who designs lighting for theater and designs cryptic crossword puzzles and was friends with Sondheim. And Richard Maltby, a fellow lyricist who learned how to do cryptic crosswords from Sondheim in the 1960s and took over for him at New York Magazine. And then Michael Mitnick, who’s the world’s largest Sondheim collector and is also a playwright and knew Sondheim. I brought them all together, and I said, I need 3 hours of your time. We’re going to reenact it.”

Joseph asked his group of solvers to work through each of the puzzles and share their thoughts as they did so. The process was revealing.

“We would analyze each clue from their perspective,” Joseph said. “Knowing Sondheim and having just solved the puzzle, what does that puzzle tell you about him? What does its design tell you about how he was designing for people? What does it tell you about his personality and how he thinks?”

“What they would do is talk about, ‘When he did this, he was being generous. He didn’t need to do that. He could have just done this part, but by adding this piece, it made it more accessible.‘ Someone would be like, ‘Oh, this one’s insidious! I could see him laughing to himself when he was doing this, thinking, oh, I’m gonna torture them with this one.’

“So we saw how that was coming through, and then we could talk about the whole experience and the overall design of it, and how all the 12 clues and puzzles fit together, and how that reflected how he wanted to engage with people in his life.”

Joseph and his solving team played through several of Sondheim’s treasure hunts, allowing them to follow the through-lines of his puzzle design work. They also identified different types of puzzles that Sondheim enjoyed and iterated upon, in one case even linking it back to its first appearance in a Will Shortz Games magazine puzzle. Through this process, Joseph was able to gain insight into Sondheim’s personality and design sensibilities. And by looking at the breadth of his work, Joseph was able to explore Sondheim’s point of view as an artist — and as a person.

“Often [Sondheim] would say, ‘Order out of chaos,’” Joseph said. “That’s what art’s about. The world is chaotic, we’re gonna create order from it. That’s what puzzles do. You’re looking at a bunch of clues in a puzzle or jigsaw puzzle pieces that make no sense. You solve the clues, and you put them in the crossword grid. You put the pieces of jigsaw together. It all comes to order. You have these moments of clarity.

“Games are about creating connections between people. … What that got me to, after all my hours of interviews with over 60 people who knew him, and studying his puzzle game designs and his game board designs, is that he was someone who was so brilliant. He thought in ways different from everyone else. He wanted to connect with people at that level, and he had to put up barriers as a celebrity and as someone who had to deal with people who didn’t communicate and think in that way throughout his life.

“And so he put up barriers, and those barriers were challenges. They didn’t say, ‘Go away from me.’ They said, ‘I’m going to give you a test.’ And the puzzles were those tests. If you could step up to the challenge and conquer it, then it was an invitation to come in and be part of his world and be close with him. If you could do that, then you became part of his world.

“And even though he’s not around anymore, those invitations are still with us. We still have his personality and his design practices and his way of thinking encoded in his designs. And we have the opportunity and the privilege to get to be engaged with them, whether it’s something that blows your mind like a cryptocross puzzle and is beyond most of us or something more accessible like a treasure hunt clue, we get to feel a connection with him.”

“Matching Minds with Sondheim: The Puzzles and Games of the Broadway Legend” will be released in May of 2025 with Applause Books. Pre-order the book from the publisher or Amazon and learn more at the web site MatchingMindswithSondheim.com and on Instagram.

If you enjoyed this interview, please consider supporting me and my work on the Center for Immersive Arts with a recurring pledge on Patreon.

As a bonus, as a Patreon supporter, you’ll also get exclusive access to my breakdown of the scavenger hunt puzzle game in Sondheim’s 1973 murder mystery film, The Last of Sheila.

The Center for Immersive Arts is reader-supported. When you buy through links on this site, I may earn an affiliate commission.

Leave a Reply